Mallott Lab Microbial ecology and human health

Research

How do environmental exposures impact the human gut microbiome?

Pathogen exposure, pollutants, flooding, and the gut microbiome.

Neglected tropical diseases were common in the southern United States well into the mid-20th century and may still persist today. In collaboration with the REACH study, we are examining how parasite exposure impacts the gut microbiome, growth, and development in children in the rural South and ex-urban areas of the Midwest. We have found that intestinal helminth infection and high levels of intestinal inflammation are not uncommon in this community [1,2] and are currently working to understand bacteria-parasite interactions in this setting.

Additionally, the legacies of heavy industry and agriculture linger in the soils of many U.S. communities. We are examining how small-scale flooding impacts soil lead levels, soil microbial communities, and the human microbiome in these same communities. In collaboration with Dr. Claire Masteller (Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Sciences, WashU), we are integrating finescale flood models with soil and gut microbiome data to interrogate flooding->microbiome->health interactions.

[1] T Cepon-Robins, EK Mallott, I Recca, T Gildner. Evidence and effects of neglected parasitic helminth and protist infections among a small preliminary sample of children from rural Mississippi. 2023. American Journal of Human Biology 35: e23889. DOI: 10.1002/ajhb.23889

[2] T Cepon-Robins, EK Mallott, I Recca, T Gildner. Exploring biocultural determinants of intestinal health: Do resource access and parasite exposure contribute to intestinal inflammation among a preliminary sample of children in rural Mississippi? 2022. American Journal of Biological Anthropology 182: 606-619. DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.24574/

Do changes to the gut microbiome during pregnancy and lactation influence energetic status and immune function?

Reproduction and the gut microbiome.

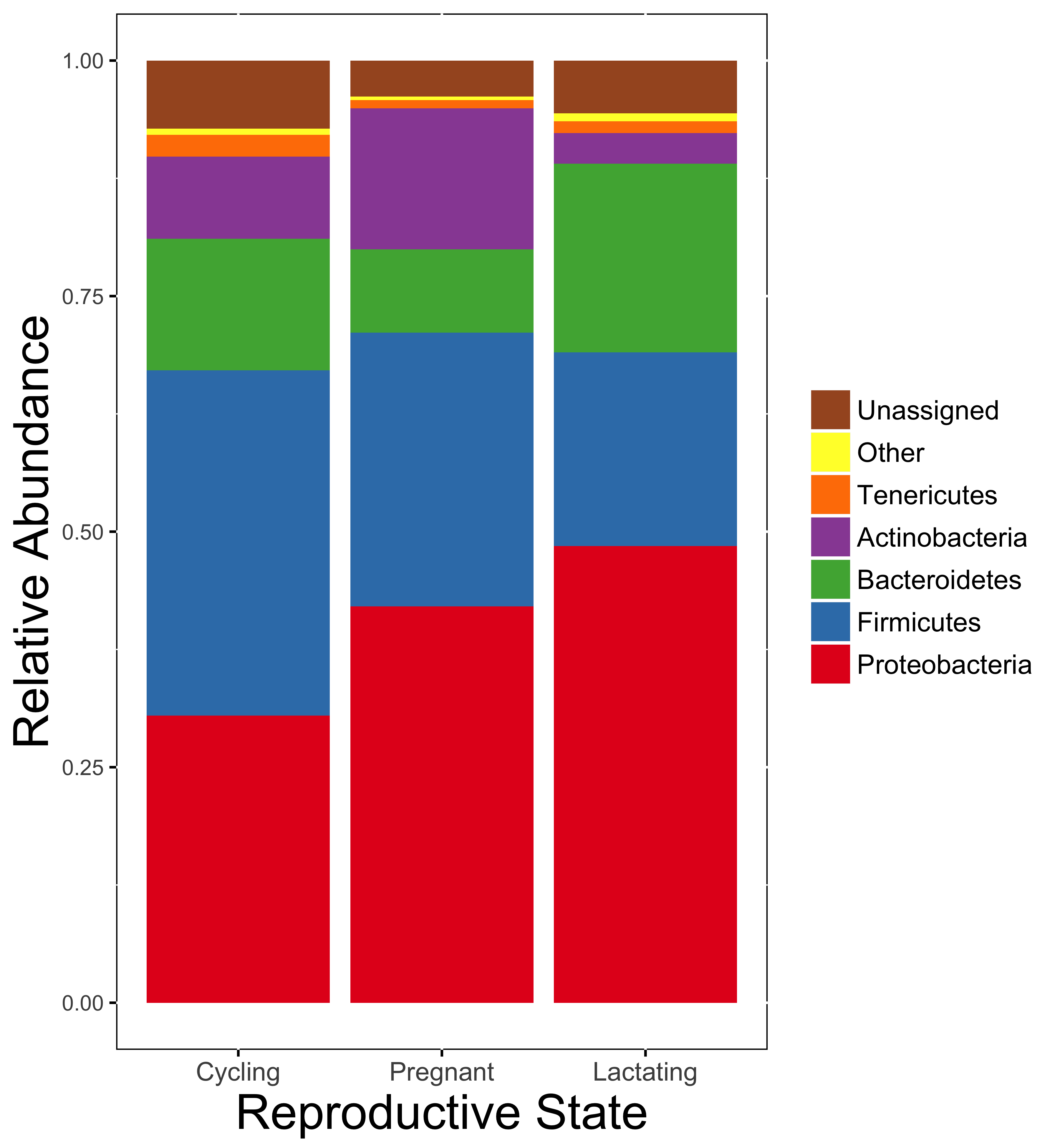

The gut microbiome compensates for nutritional shortfalls in nonhuman primates [3] and may be one strategy for buffering the energetic stress of pregnancy and lactation in female primates. Our work has shown that the composition of the gut microbiome differs across reproductive states in white-faced capuchins [4], and that progesterone may be mediating interactions between reproductive state and the gut microbiome in Phayre's leaf monkeys [5].

Gut microbiome composition across reproduction [4]

Gut microbiome composition across reproduction [4]

We are currently generating gut metagenomes from Phayre's leaf monkeys to examine finescale variation in function across reproduction to help determine if the compositional changes are increasing microbially-derived energy available to the host.

We are also examining nutrient consumption and the gut microbiome differs between breeding females, non-breeding females, and males in a cooperatively breeding primate - saddleback tamarins.

Additionally, we are recruiting a cohort of pregnant people to characterize the changes in the structure and function of the gut microbiome across pregnancy and postpartum. We are interested in how hormones and immunotolerance interact to shape the gut microbiome.

[3] EK Mallott, LH Skovmand, PA Garber, KR Amato. The faecal metabolome of black howler monkeys (Alouatta pigra) varies in response to seasonal dietary changes. 2022. Molecular Ecology 31: 4146-4161. DOI: 10.1111/mec.16559/

[4] EK Mallott, KR Amato. The microbial reproductive ecology of white-faced capuchins (Cebus capucinus). 2018. American Journal of Primatology 80: e22896. DOI: 10.1002/ajp.22896

[5] EK Mallott, C Borries, A Koenig, KR Amato, A Lu. Reproductive hormones mediate changes in the gut microbiome during pregnancy and lactation in Phayre's leaf monkeys. 2020. Scientific Reports 10: 9961. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-6685-2

What are the relative contributions of host genetics and environment to the gut microbiome?

Hybridization and the gut microbiome.

Natural hybrid zones offer a unique opportunity to disentangle the relative contributions of host genetics and environment to the gut microbiome. We are currently studying the gut microbiomes of hybridizing populations of tufted gray langurs and purple-faced langurs as part of the Kaludiyapokuna Primate Conservation and Research Center in Sri Lanka.

How has the metabolic function of the gut microbiome changed across primate evolution?

The evolutionary trajectory of the primate gut microbiome.

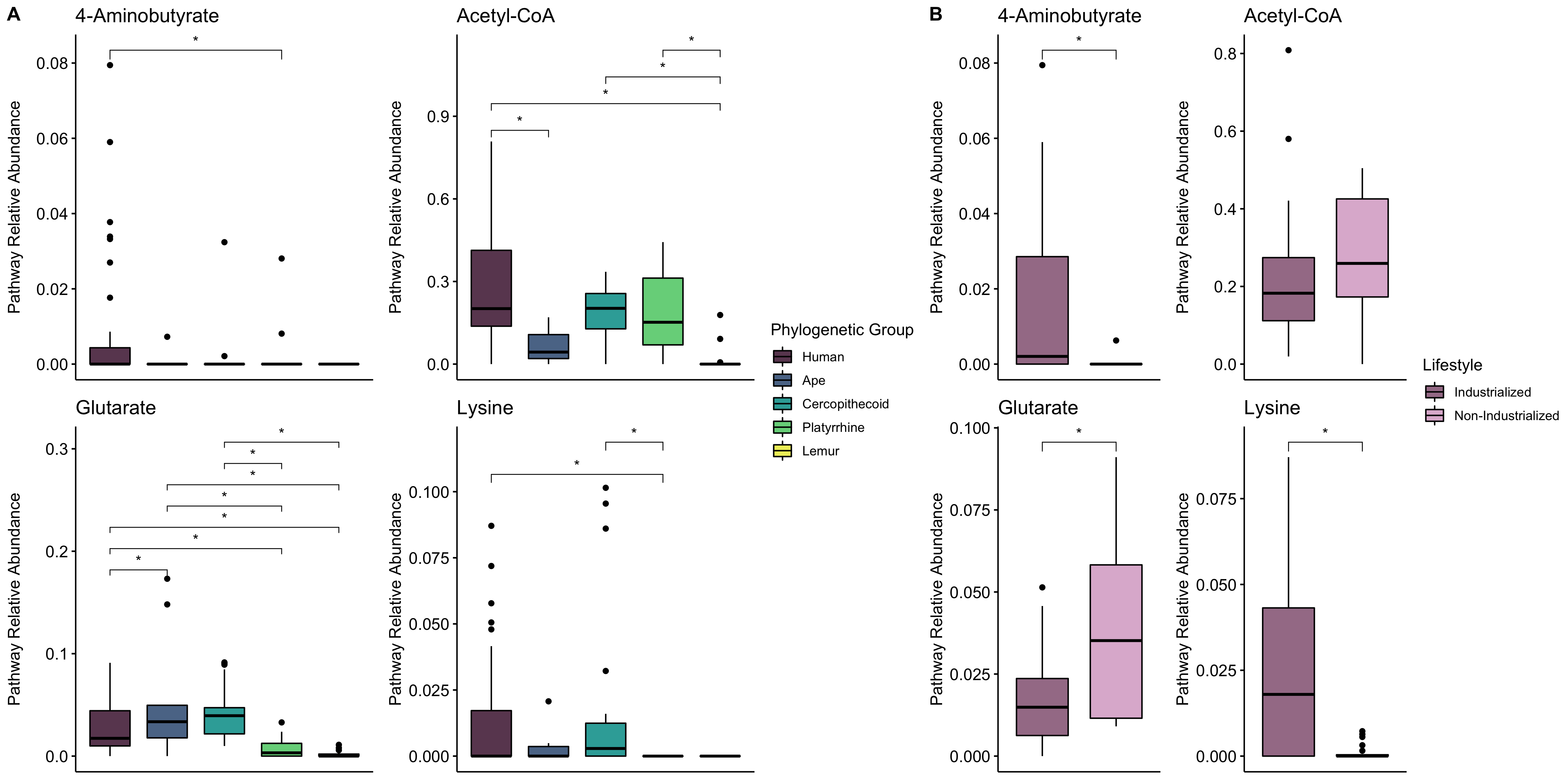

The gut microbiome of humans is distinct from that of other primates [6]. As human diets have diverged from those of other primates, the metabolic functions of the gut microbiome may also have shifted. In particular, we are interested in short chain fatty acid (SCFA) metabolism. SCFAs are produced by bacteria in the gut and can be used by the host for energy. Previous computational work showed that butyrate production potential does not differ markedly between humans and nonhuman primates, but that the pathway abundance does differ between humans in industrialized vs. nonindustrialized environments [7]. Additionally, differences in the capacity of the microbiome to produce SCFA may have implications for brain growth and development [8].

Butyrate pathway abundance differs across humans, but not between humans and other primates [6]

Butyrate pathway abundance differs across humans, but not between humans and other primates [6]

We are now using multiple molecular and microbiological methods to confirm these patterns in living humans in multiple geographic locations, several species of nonhuman primates, and ancient humans.

[6] KR Amato, EK Mallott, JE Lambert, D McDonald, A Gomez, JL Metcalf, NJ Dominy, GAO Britton, RM Stumpf, T Goldberg, SR Leigh, R Knight. The human gut microbiome is more similar to that of Old World monkeys than apes. 2019. Genome Biology 20: 201. DOI: 10.1186/s13059-019-1807-z

[7] EK Mallott, KR Amato. Butyrate-producing pathway abundances are similar in human and nonhuman primate gut microbiomes. 2022. Molecular Biology and Evolution 39: msab279. DOI: 10.1093/molbev/msab279/

[8] EK Mallott, S Kuthyar, W Lee, D Reiman, H Jiang, S Chitta, EA Waters, B Layden, R Sumagin, LD Manzanares, G-Y Yang, ML Savo Sardaro, S Gray, LE Williams, Y Dai, JP Curley, CR Haney, ER Liechty, CW Kuzawa, KR Amato. The primate gut microbiota contributes to interspecific differences in host metabolism. 2024. Microbial Genomics 10:001322. DOI: 10.1099/mgen.0.001322